The background in the image ‘You guys!’ is the wallpaper that was on the walls of the room known as ‘the breakfast room’ in the house in which I did most of my growing up.

When we cleared out the house in 2019 three years after Mum died and after finally managing to sell it I brought away with me some rolls of wallpaper that were spare and left over in the house. This particular one was not on show in any of the rooms but could still be seen covering the walls inside a built-in cupboard in the breakfast room. It was a bit of a revelation when we cleared out all the old bits of china and crockery that was stored in there and the orange and yellow pattern came to light.

With these remains of the old rolls of paper and some carpet remnants left over from the upstairs landing, a striking Greek key pattern in navy and scarlet, I had attempted in the couple of years before working on ‘Palimpself’, to put together sections of the wallpapers and carpet in small pieces to make a wall panel that would be reminiscent of the house. My intention had been to make three the same, to keep one for myself and to gift the other two to my two older sisters so that we would all have the same piece hanging in our homes that would connect us to our parents’ house.

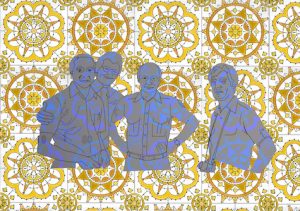

Trying to fathom a combination of these swatches when each bore such distinctive and brightly coloured patterns was challenging and I experienced two phases of engaging with them and making attempts to do so before giving up temporarily on this aim. The breakfast room wallpaper asserted itself when I was making the images for ‘Palimpself’ as a suitable background for the four men in their seventies’ large-collared shirts and swagger. The men were housed in a photograph taken by my Dad on one of his business trips abroad and found by me when going through his old photos looking for interesting images. The boldness of the pattern and the colours in this paper would convey, so went my thinking, something of their ability to put themselves across with ease to make a picture that might ‘jazz’ with the eyes, making the viewer confront this wallpaper pattern, which would have these men built into it.

As I played around with the outline drawing of the men and the scan of the paper, they came into the foreground and receded back into the support depending on which colours I chose to transform the oranges and yellows into. I found a way in which, when the figures of the men were placed in layers over the background, the place where the wallpaper filled their shirts and bodies flipped to contrasting blues and lilacs so that the pattern of the paper became the pattern of their shirts. The wallpaper background was as loud as the designs on their shirts so that they were part of the background of everyday life as well as shouting out from it that they were there, a bit like men in the seventies asserting their presence against a burgeoning second wave of feminism, trying to consolidate dominance against fears of being swallowed up.

In using elements in the images, which, when I look at them hold a strong emotional resonance for myself and putting them into combinations with drawings of figures or people cut from old photographs, some of which hold similarly powerful personal associations for me and others not, and taking them to the point where the image ‘works’ in some way, where I can say ‘c’est ça’, I am hoping that the reverberations inhering in the very personal elements will come through. I am trusting that the overall effect of the image to a viewer who does not share any of the specific connections to particular motifs, figures or patterns that I have, will be to allow that viewer to pick up somehow on a residual ‘charge’ gained from the personal investment I have put into the making of each image.

The images are fictions but their fabric contains aspects from my life.

This post is a way in to the blog I have kept throughout the project ‘Palimpself’, a University of St Andrews commission, making new work in response to the writings of Annie Ernaux. It charts the development of the ideas for work, images and observations collected along the way, interactions with my collaborators Elise Hugueny-Léger and Fabien Arribert-Narce, dreams, early morning ramblings, and the otherwise generally uncategorisable.

Detail of ‘Chose’ adapted as basis for the exhibition poster

A blog is, in a sense, a kind of palimpsest, if a ‘palimpsest’ is a text written on top of another, the original having been scratched out or retained. One post gets written only to be overwritten by another, more recent one. The chronology of a blog usually starts at the top of the page with whatever has been newly posted and scrolling down into the mulch of earlier days, months, years, you can find earlier entries, superseded by what comes after.

I decided to write this introductory ‘entry post’ to the blog when I realised that the one I was previously giving a link to, called ‘Architectures of Possibility’, which I felt gave a good introduction to the context of the Byre Theatre, was, in terms of where it came in time, rather compromised by being about my first visit to St Andrews last April, but written up just under a week ago, in September.

The Byre Theatre, part of the University of St Andrews

I have already, it seems, disrupted the intended order of this blog when it comes to time but rather than try to sort that out, somehow, by pretending that the post I wrote last week, about some days in the Spring, was an April entry, jiggling around with the dates and reorganising the posts by doing something clever with the organisation of the order in which they appear, I’ve decided just to let it all be, as it is. So, just to say, you’re starting here but there might be some posts following on from this as the days progress and we start setting up the exhibition, then launching it, then doing the Byre World talk on 9th October. They’ll be at the top, likely under the heading ‘Recent Posts”.

You can scroll back to any months from February of this year, the start of the commission, to by looking down the left-hand side of the screen under the heading ‘Archive’ and see how the development of the works and my collaboration with Elise and Fabien have progressed through time. Should you get lost in the depths of my website, then returning to the option ‘Palimpself’ on the top menu bar should set you back on the right track.

Cut out from an archive photograph of a storeroom in the Byre Theatre’s early days

Time is so far from being linear as it is lived. It is not coherent, not one thing, it loops and curves, jumps, stops and starts. Memory joins some of it up as does anticipation but these also serve to derail it, often necessarily so, preventing life from being too predictable or making too much sense. A blog as a document is a permanent first draft, growing up towards the light. This is not to excuse it but only to say that it becomes what it is, through time, whatever that might be.

If you’d like to ask me anything about any aspect of the project or get in touch with a question or an enquiry about any of the works you can do so here: info@susandiab.com

Thank you for your interest

À bientôt!

I’m not sure how to begin this post. One thought immediately is a strong contrast I have noticed between myself and Ernaux’s writing. In Ernaux there is an absolute lack of sentimentality. Actually, no, I’ll take that back. There are moments and I’m trying to locate one in my mind, perhaps the mention of the yellow forsythia she takes for her Mother when she visits her in the care home. (‘I Remain In Darkness’, ‘Je ne suis pas sortie de ma nuit’). The sentimentality there is maybe overridden by the image of the forsythia as it asserts itself in your mind, the colour, that yellow, and it becomes a gesture of love. There is a cut off point between sentiment and sentimentality. I think I could think of more sentimental moments if I tried and I promise to. The contrast I spoke of is between that scarcity of sentimentality in Ernaux and the bucketloads I know to exist in myself when I feel affection for others.

Intellectual companionship, the meeting of like-minded individuals in common purpose and friendship.

Allow me to introduce them:

Dr Élise Hugueny-Léger, Senior Lecturer in French in the School of Modern Languages, University of St Andrews. She is brilliant. Her research profile is here: https://research-portal.st-andrews.ac.uk/en/persons/elise-simone-marie-hugueny-leger

Dr Fabien Arribert-Narce, Senior Lecturer in French and Francophone Studies in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures, University of Edinburgh. He is brilliant. His research profile is here: https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/persons/fabien-arribert-narce/

On my first site visit to The Byre I was looking round the theatre on the day of meeting them for the first time at midday . I looked at my watch, they were due to show up there to meet me five minutes later. A second later a young man, presumably a student, started playing the piano on Level One. My knowledge of classical music is extremely limited but I recognised the tune at once and its name came to mind: ‘Für Élise’ (‘For Élise’). How strange, you couldn’t make it up.

We met. These two who had the idea in the first place to try to raise funding to commission me to make new work as a contribution to this year’s Ernaux conference, an idea which prompted this so significant and to me so seminal project. Generosity. In them. In Ernaux’s writing. An openness to possibility in others, a willingness to risk it.

We walked round the building, we went for lunch, we visited the Wardlaw Museum where Élise took us up onto a small roof terrace to look out to sea. Limitless horizons.

Once a month since January we have met up online for a generous hour to discuss the development of the work, exchange thoughts and ideas from our readings of Ernaux and related secondary literature, settle practical matters and enjoy each other’s company. Their insights and creativity as collaborators have contributed so much to what the exhibition has become.

You two, thank you. Merci beaucoup.

I went to St Andrews in April to visit The Byre Theatre to understand its shape and character. I found a beautiful building, much larger than I had imagined from the initial photos that Jan* had sent me. The photos gave a good sense of the detail of the place but not of the scale of the building. I was intrigued by its having seemingly two entrances, one via a ‘wynd’ or narrow passageway from South Street, which takes you through a pretty garden to the Box Office entrance and the other, larger entrance on Abbey Street.

The latter looks more like the front of the building as it gives onto the street but it is where access to the back of the stage can be found, by means of a large sliding door for easy delivery of stage sets, equipment and so on. I’m writing this with hindsight, having understood much more about the building by now and the use of the different parts of the building were not apparent on this first visit.

I noticed a hushed interior with students seated at small tables getting on with their studies, mostly individually but some in small groups working quietly together. The place had an atmosphere of calm, rather like a library, which I am sure is quite different before and after a performance in the theatre with large numbers of people passing through.

I was able to move through the four levels using the iron staircase and travelling back down to ground floor, or Level One by means of the lift. I noticed wood, glass and stone as the primary materials but also metal, black ironwork in the detail. A sense of the outside coming in with a view to the small, sloping garden through the large double window on Level One.

What I hadn’t anticipated before arriving in the theatre was the rush of ideas I would have with this visit. Having spent almost three months immersing myself in Ernaux and beginning to devise work for the spaces and imagining what it might be but without first-hand knowledge of what it is like to be in that environment, a vacuum had formed into which the ideas flew, some ready-formed, taking their place in specific areas or corners and presenting themselves to me clear as anything so that I could see them in my mind’s eye. They sort of announced themselves to me, one after another, spreading their arms, looking at me and beaming “ta-dah! meet ME, I belong here” they seemed to say, pointing to a particular spot.

I came away from that visit with at least fifteen completely new ideas for pieces of work, whereas previous to my site visit I had been working to one main one. I couldn’t write them down or draw them quickly enough in my notebook.

My head full and feeling elated I left the Byre when it closed to the public at 5pm and took myself off to the sea, walking around the ruins of the cathedral with its imposing double-horned tower glaring down accusingly at me. As I negotiated the walkways and walls of these ruins of Reformation zeal I could feel a barely repressed Catholic energy emanating from their stones like the warmth from the Spring sunshine. It was a beautiful day, clear blue sky, fresh coolish air, a sweet breeze coming in from the sea. I stopped to look over the cliff edge down to the waves as they lapped the rocks below and saw the reflection of the tower on the surface of the water, like a fiendish beast, delineated by the setting sun caught behind the H of the ruined tower.

I brought that new stock of thoughts and ideas back with me and then was tasked with fitting them into the realm of possibility. A living, breathing, multi-functional building like the Byre, with its various constituencies of people using and inhabiting it has ‘go’ and ‘no-go’ zones and areas. I had mentally hung a sky-blue velvet curtain on the large white brackets of the large wall in the Abbey Street entrance, saw it waving in the sea breezes, erected fresh, wet, clay figures in amongst the stones of the sloping garden, seen them dissolve in the rain and become one with the ground, stood free-standing sculptures of varying dimensions and meanings on the different levels, viewable from ledges, balconies and when coming around corners. I had made a writing desk for Annie Ernaux on Level 4 with views out over the rooftops of St Andrews, filled the bookcase on Level 1 with a complete set of her works, in French and English.

My imagination and the possibilities on offer to it were limitless. One day, after the visit, I had a moment sitting on the sofa in our living room at home. I felt a door open onto a much larger world and imagined, for a moment, working to a much grander scale than I had previously. That is yet to come, for an appropriate place. For the time being, the human scale fits better with the safety and wellbeing of the people whose regular knowledge of the Byre takes precedence. But I’ve seen through that door and I can’t go back.

*Jan McTaggart, Deputy Director of The Byre Theatre

20 June 2024 Summer Solstice, the longest day of the year

My dear Elise and Fabien

It is gone 1am and I ought to be asleep. Tomorrow morning, Friday, John, my husband and I go to a singing group and I’ll be tired if I don’t get to bed and to sleep soon. However, as I was turning over in bed I was composing sentences to say to you both and so I thought the best thing would be to get up and write them down, then, once written, I’ll be able to get off to sleep. At least that’s what I hope.

Before I got to that point of deciding to get up and write to you I was composing ideas for the rug piece to go on the wooden platform on the ground floor of the Byre, the space next to the big rock or ‘anvil stone’ that was dug up when they were excavating the ground for the foundations of the new Byre building. I’ve not fully resolved that piece yet in my mind, but I know that I will. For a time now I’ve had it as a carpet, the same size as the top of the platform, with ‘C’est ça’ written on it, which is what Annie Ernaux says she thinks when she’s written something just as it needs to be (in ‘Le Vrai Lieu’), when she knows she’s got it right. This afternoon in my studio I began some tests on some carpet. I filled a wine glass with wine and then deliberately knocked it over, with a gesture of my hand, as if I were in conversation and gesticulating and forgot myself and knocked the glass over. It made a pleasing spill shape on the carpet and I was quite pleased with it. It felt transgressive to knock over a glass of wine deliberately. (Don’t worry, it was very cheap wine, Sainsbury’s Not Finest, £3.49 a bottle)

Then I made another addition to the carpet by unscrewing the top of a pot of red nail varnish and quickly pouring it back and forth across the carpet as if I were decorating a cake with icing in a Jackson Pollock style, trying to achieve a kind of randomness, which is always difficult. The red nail varnish looked good, a convincing scarlet, on the carpet, which is a light grey, just what they gave me in the shop to experiment on. Then I had been thinking of having the red drizzled all around the letters of ‘C’est ça’ so I was looking around for some shapes I could use as a kind of stencil to spill the red nail varnish across so that when I removed the shapes there would be just carpet with the red all around the outline. Amongst the heaps of stuff, tools and god-knows-what that is currently scattered all over my long table in my studio my eyes fell on two bags of unconsecrated hosts from the Catholic mass, one bag of small-sized ones and another of a larger size. I bought these at least fifteen years ago from an online Catholic supplies company. So I used them! It’s so strange, how often actions seem to take place by chance but then there is a kind of logic to them. The hosts laid on the carpet ‘pinned down’ by wavy lines of red nail varnish next to a spill of red wine seemed like the leftovers after some kind of teenage-party-cum-Catholic-rite-of-passage-ceremony, which all seems very appropriate.

Actually, thinking about that now it feels as if the tests themselves could become the work, as I initially conceived of it as a messy spillage, brought to mind by the spot of red blood evident in the otherwise clean bowl of every single one of the ladies’ toilets in the Byre Theatre, that morning of the whole day I spent there in late April. The day I met you both. Also, on my way to the theatre that morning I had walked along South Street and stopped to call in on an oriental carpet shop because they had one very like my family heirloom Persian rug in the window. I had a nice long chat with the owner of the shop and we discussed the recurring motif in the rug he had in his window and on mine and I had showed him photos of my rug on my phone. The particular recurring motif they both shared was the ‘gol’ or ‘gul’, from the Persian for ‘flower’ or ‘rose’:

(source of image: https://persianrugvillage.com/the-language-of-motifs/ accessed 20/6/2024)

An aside: as I was coming down the stairs to write this to you both, I had the thought that I could write to you in English but pretend that I was writing in French. I could say to you something along the lines of “isn’t it marvellous how my French has improved since I wrote that piece for you in French recently about my humiliation at aged sixteen by the mean Belgian man. He derided my youthful French and gave me a complex ever since, which I have spent a lifetime trying to shake off. But now, since writing about that incident, my French has shaken off all its fetters and is so relaxed and easy that it just feels to me like writing in English. That I could pretend that this writing here, now, is French, not English at all.

Would you buy that, I wonder?

Before I switched off my light to go to sleep, before I tossed and turned and then decided to get up and write to you, I had been reading ‘Anna Karenina’. I’ve only just started to read it and it’s the first time in my life that I’m reading it. I don’t know why but I feel slightly ashamed of that fact. Ernaux mentions Anna ‘Karenina’ more than once in her work as being significant to her, particularly in forming her fascination with Russian culture. I’ve read – and studied – some of the other major novels of ‘female experience’ by male authors: Madame Bovary, naturally, Effi Briest by Fontane. I bought this edition of Anna Karenina in a charity shop last month for a couple of quid. It’s a really nice hardback edition from 1977, pleasingly heavy in weight, still with an intact dust jacket, published by Heinemann and on the back cover there are some photographs of a BBC TV production of ‘Anna Karenina’ starring Nicola Pagett. I was thinking about them, as actors playing characters from a fiction created by Tolstoy. And I was thinking about acting, about fiction and about pretending in general and then I started thinking about all those activities in relation to Catholicism and confession and the messages I picked up as a child about not lying, as if that were a sin in itself. Actually – I’ve just googled what the cardinal sins are and lying is not one of them. The comedian Paul Merton, whose humour I love, once said when I saw him on stage, that being raised Catholic had been quite an obstacle to him when he started in drama because he’d confused making stuff up with lying after an angry nun had told him off for spinning some kind of fiction to her when he was very little. And so of course, I got thinking about Ernaux and her ‘truth’ and the need to get to the truth in relation to memory and experience. And her Catholic, though seemingly not particularly religious upbringing.

So, yes, anyway, I’m still writing in French. It’s good isn’t it, how fluent I have become. It’s as if there is no difference to me between English and French. I have just morphed as easily as breathing into this completely natural French speaker (in my dreams . . . ). But, importantly, I have also been noting that since the piece about my ‘Verdruß’*, I have been writing to you less, which has also been partly on account of being so busy with the practicalities of making the work for the exhibition. And I don’t want to restrict what was previously a very free-flowing line of communication with you both.

* a German word from Goethe’s youthful novel ‘Die Leiden Des Jungen Werther’, The Sorrows of Young Werther, denoting the humiliation the young eponymous hero suffers at court.

So maybe pretending that I’m writing in French, while actually writing in English gives me a way to write everything I want to say to you both in an unfettered and less guilty way than if I just speak and write English all the time?

That was all an aside. The point about calling in on the rug shop on my way to the Byre is to bring in some of the reds from the carpets I saw there and see in my own ‘gul’ patterned rug, in combination with the spots of blood, into the carpet piece to go on the wooden platform.

The significance of the ‘Persian’ rug being that it forms a link to my Father’s side of the family, his Father’s, my Grandfather’s Armenian heritage and a host of stories I don’t have access to, which have got lost and are now untold.

Uncovering. Perhaps that’s a key word for this project, this wonder-full, fascinating, all-involving investigation about Ernaux, sculpture, languages, cultures, writing, connections, relationships, global histories, diaspora, images, palimpsests, materials. Everything.

And the new idea for the carpet piece, I’ll just briefly try to write about that here before I head upstairs and try to get back to sleep so that I’m not nodding off too often in our singing group in the morning. It is images of objects from the first image I started to work with, which I found back in December or January in the online archive of the Byre Theatre. It’s a faded photograph of what looks like a storeroom or props room. “Memory is a lunatic props mistress” one of my favourite quotes from Ernaux from ‘A Girl’s Story’ (just tried to look up the French in ‘Mémoire de Fille’ but don’t think I’ve even got a copy of this in French, must rectify.) Some of the key objects in the image are cut out, printed onto flat, inflexible card or thin plywood, over the top of a soft pocket, like a sock or equivalent, sitting on top of the carpet on the platform, which is now a black carpet, for the darkness, I presume, out of which ideas, memories, experiences emerge as they are recalled. Each is weighted down with a small cobble or rock, contained inside the pocket so that the images of the partial or indistinct objects do not all lie flat on the same picture plane but are at slightly different angles to it and will reflect the light coming through the treads of the staircase differently. I’m thinking, the carpet could be an enlarged ‘gul’, the same reds as my own carpet. A rose or flower through which the objects emerge, like their neighbour, the anvil stone. I can see this piece now, so clearly. It is asserting itself. It’s better, more mysterious, thus more evocative and allowing for more imaginative interplay with the viewer’s mind than the simple statement ‘C’est ça’, which becomes, of course, its title.

I hope you don’t find this rather long and in-depth ‘going-into’ of some of the processes of how ideas for a piece are developed too indulgent and that instead you enjoy reading them. Writing this gives me a way to let you into this fertile and intense making period, to share it with you, allowing me to let those mental conversations with you, which I’ve been having for a few weeks now, be actual conversations, conveyed albeit with a delay but shared nonetheless.

Finish 02:35am Friday 21 June

Mon français se trouve – si je peux emprunter une analogie à Ernaux – sous un rocher au fond d’une rivière. Je vous raconterai une histoire triste qui finit bien. J’ai choisi de vous révéler, vous Elise et Fabien, ce qui s’est passé, parce que vous êtes les facilitateurs de notre projet qui m’a offert l’occasion de pouvoir réunir en ce moment de ma vie mes deux grandes joies, les langues et l’art. J’espère, en relatant ce qui s’est passé, d’être libérée de ses conséquences et renait comme une personne qui peut parler français avec plaisir et plus d’assurance.

Quand j’avais seize ans mon école m’avait recommandée aux autorités locales pour un prix en allemand parce que j’avais fait de bons progrès en ce sujet. Le prix consistait en une somme d’argent pour passer un mois entier pendant les grandes vacances en Allemagne pour suivre un cours d’allemand. C’était une bonne opportunité et je jouissais du sentiment d’avoir achevé un peu de reconnaissance pour mes efforts. Ce serait la première fois que je voyagerai seule à l’étranger et c’était pour moi une grande aventure.

Munich. Le commencement du cours. Après un matin d’introductions, nous élèves se rassemblent dans McDonalds au rez-de-chaussée du bâtiment où se trouvent l’école de langue. L’atmosphère est maintenant plus informelle que pendant la classe et nous partageons entre nous des informations sur nos vies.

Il y a un étudiant qui vient de Belgique. Il est un peu plus âgé que les autres participants et s’appelle Antoine. Il parle français avec les autres du groupe. Enthousiaste pour pratiquer mon français ainsi que mon allemand je l’adresse en français et lui raconte un peu de ma vie et les circonstances de mon logement pendant mon séjour en Munich.

Quand je finis de parler il me regarde d’un air qui m’est peu connu. Il rejette la tête en arrière et rit d’une façon moqueuse: « Mais Suzanne, votre français est horrible! »

Le rocher descend sur moi et m’écrase. Depuis ce moment-là, il y a quarante-quatre ans, mon français a souffert sous son poids. J’ai fait ce que devais faire pour obtenir mon diplôme mais je n’ai jamais retrouvé la jouissance en français que je possédais avant cet entretien avec cet Antoine.

Jusqu’aujourd’hui. Avec votre amitié et encouragement, avec le démontage méticuleux de la honte dans les œuvres d’Ernaux, avec les possibilités que m’offert ma propre créativité, la pierre lourde sur ma langue se dissout comme un bonbon amer.

Peut-être que je puisse rentrer dans le monde des parleurs de votre langue si belle et si miraculeuse . . .

Merci beaucoup Elise et Fabien !

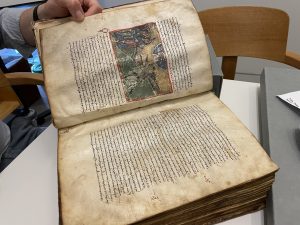

Meeting with Peter Tóth, Curator of Greek Manuscripts, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Tuesday 14th May, 1.oopm

The unglazed side of the pottery was used to write upon. After the second use of a shard, it would be thrown away thus large numbers of this kind of palimpsest can be found on ancient rubbish tips.

Greek schoolchildren would use them for their homework. An entire homily (sermon) was written on a shard. Homer used them to write on.

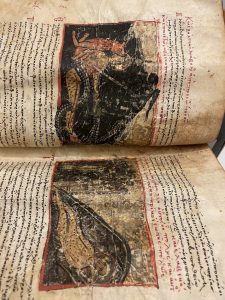

Palimpsests viewed and discussed at our meeting:

Wax ‘slate’ palimpsests were used with a stylus to write upon. Peter used a modern remake of one to demonstrate how it would have been used, the flattened end would have been heated and used to smooth over the wax to erase previous marks. This object, two wooden blocks, tied together at the spine with leather thongs clearly show how the book form derived from them. Tablets such as these would have been widely used within administrative operations. Sometimes people would press so hard into the wax that they would make impressions in the wood underneath, which can also be interpreted and read.

The word ‘palimpsest’ is from the Greek meaning ‘scraping again’. Peter contends that if you cannot see the undertext you would not call a document a ‘palimpsest’. It is the undertext that he, personally, is most interested in and part of his work is to decipher what the undertext says. Peter explained the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the Pharoahs and from that time on papyrus was used. A shift was also made from hieroglyphs to demotic language. Hieroglyphs were sacred, were meant to be forever and represented the language of the gods. Demotic language was cursive, much more hurriedly written and became widely used in literature. An example is the Ancient Egyptian owl, which was a very beautiful drawing of an owl. With the shift to cursive it was represented by a curved line. Demotic, cursive language could be understood by everybody. Alexander the Great’s conquering of Egypt brought with it the widespread use of Greek as the official language of administration. Greek papyruses stem from the seventh century but from the fifth century onwards Latin was growing as the dominant language under Roman rule.

In recent years advances in visual imaging techniques are making possible readings of palimpsested undertexts. An example of a project seeking to read, interpret and understand palimpsests is the Sinai Palimpsests Project:

https://sinai.library.ucla.edu/

Bel and the dragon; Grammatical text; Homily, 3rd century – 5th century, Egyptian, Greek and Latin, parchment

12th – 13th century parchment codex telling the story of Job with illustrations

The sons of God present themselves before God. Satan. (Job 1, 6-7).

Job covered with boils. (Job 2, 7)

Questions I prepared to put to Peter. Some of these were answered by Peter in conversation as above. The remaining ones I shall put to him via email now.

- Is there a correct definition of ‘palimpsest’ or can the term be used as loosely as it is?

- What differentiates palimpsests of images from those of texts?

- What is the type and range of materials and media used for palimpsests?

- Are there examples of palimpsests where a writer was trying to perfect or improve upon their text by writing over it?

- Are you aware of other artists who make work as palimpsests?

- What do you like or enjoy about palimpsests?

- What is their principle difficulty?

- What makes a palimpsest interesting to you?

- What would be your question to ask of or about a palimpsest?

- What was the third example of a palimpsest you were going to show me but which we ran out of time to view?

Answers to my questions sent to me by email by Peter Toth:

- What differentiates palimpsests of images from those of texts?

Nothing really, the idea is the same, to erase something to be overwritten by something else. Maybe the nuance is that images are often erased with some intention on top of the practical consideration of getting a cheap new page (which is often the case with texts). There is often a specific reason why they decide to get rid off the original image: we saw that representations of the devil are often scratched out (fear/hate against seeing him), images of unwanted people, saints disliked later (Beckett was often erased from MSS during the reign of Henry VIII) etc.

- Are there examples of palimpsests where a writer was trying to perfect or improve upon their text by writing over it?

I am sure they are but it is very rare with a whole page or sheet. What usually happens is that they erase a word with a typo or mistake and write the correct one instead, on top. But I haven’t seen this in a unit more than a line but that is already very rare. In case a larger amount of text was thought to be superfluous they simply cross it and start again. See Thomas Aquinas’s handwriting here https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.9851/0051

- Are you aware of other artists who make work as palimpsests?

I am not the right person to ask about this, I am not very familiar with contemporary art but I am sure there are others approaching this theme from various angles. Gerard Genette would be important to refer to in this context…

- What would be your question to ask of or about a palimpsest?

I am always selfish in this situation. I want to know what the undertext exactly is, what is its date and relationship to other manuscripts of the same text to assess the value and position of the earlier undertext. It is only after this, that I would try to find out what the undertext has to do with the upper text and if there was any specific reason why it was decided to be erased.

- What was the third example of a palimpsest you were going to show me but which we ran out of time to view?

I think it was a Latin palimpsest which we could not see Ms. Laud. Misc. 391, f. 57-64 but that is fully digitised so easy to compensate for see it here https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/c2ed1c10-4520-4b4f-b0e2-8ba6e0720890/surfaces/44aa2b54-94b9-4d31-94b5-db4ffc93ac6a/ By all means do take a look at the brilliant project at the Sinai Monastery digitising all their palimpsests and making major discoveries. It is all online at https://sinai.library.ucla.edu/ you need to register but it is easy and free.

Some notes 4am Saturday 27 April 2024

Since I wrote these notes on Saturday morning, everything has moved on a lot further

Returned from research trip to St Andrews yesterday afternoon.

Ideas going through my head right now.

Stream Of Consciousness SOC

Le SOCle – plinth, base, pedestal

Sock

SOC(k)

Could rope off the small desk area on LG where there is wall space to create a free-standing space

Rug, what is rug in French? Tapis? Tapiès. Could do footprints in memory of Ana Mendieta, wasn’t she murdered by Carl André? Whatever happened to that? Read more about that case.

I like the word ‘rug’, it’s so short and ‘ug’ like.

Let my love of puns roam free.

Free-standing, as opposed to being charged for standing.

Can buy AE books second hand for as cheap as can get them, or, invite conference delegates to donate one each and then see what we get, so a random selection, doesn’t matter if they’re annotated, in fact, if they are, so much the better. And ask the local bookshop to provide some in exchange for publicity.

How my mind races, I’ve now got a whole space to imbue with A E

I was reading about the letter Ash on the train yesterday, it looks like A and E joined together. A and E, Annie Ernaux, Accident and Emergency. AutoEthnography. It is one of the ten obsolete letters of the alphabet.

Æ æ

Ash, H in French, aitch, or the now frequent English Haitch ‘ate?

language continually evolving and changing

you can’t hold onto it, it runs away

I like what Jesse Darling says here (https://www.the-berliner.com/art/jesse-darling-interview-turner-prize-winner-berlin-british/) about being freer with the German language, about not being restricted to it being how it’s supposed to be. I am a real stickler for grammar and knowing how the ‘bare bones’ of a language work, which I believe gives you much more freedom to use the language because it gives you an understanding of how it works. Our English teacher at school, Miss B, who taught us so much about the English language, which gave me such an advantage when it came to languages. I don’t know that I have ever played fast and loose with the German language, though I am always doing it on my own.

Playing fast and loose.

Fast and loose – Is that a piece of music, a tune?

Let language split open, go into that.

Or rather let it all fall out

Art and puns. Art and mad language. The Surrealists were into all that. Art and Language. Art and languages

Don’t worry too much about that, do it my way.

Frank Sinatra

Sintra – a municipality in Portugal, just googled it, there’s a mad yellow and red painted castle there it seems (called Pena, Spanish for ‘pain’) and a site entitled ‘How long do you need in Sintra?’*

How long do you need in a place? In a world? In life? How long does anyone really need to live their life? If you could have a particular length of life, how long would it be? If you could have unlimited time? Would you like to live forever if you could? People usually say “If I could keep my health”. Then they start getting preoccupied with holding onto their youth. As if you have to look beautiful forever. Who gives a stuff what you look like if you’re having a good time?

*Neuschwanstein, I’ve got a book about Ludwig somewhere. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. My old friend CB was from Füssen. I looked him up on the journey to St A, he’s still around, being an artist, living and working in Hamburg still. Must contact him. Downloaded a pic of him to my phone. He looks just the same, just a dusting of icing sugar around the edges of his face.

I hate this fashion for cosmetically interfered with lips which look like rubber.

Do people who’ve had ‘designer vaginas’ get their labia inflated? Pumped up with liquid fat from other parts of their bodies they’d like less big? And if so, can they sit down comfortably? Remember Annette Messager’s work, whatever happened to her? What is she doing/making now? Just looked her up. I never realised she had been married to Christian Boltanski. She’s 80 now. https://www.mariangoodman.com/viewing-room/annette-messager-frieze-ny-2021/

This needs saying again:

Who gives a stuff what you look like if you’re having a good time?

Giving a stuff.

‘Turgid’ when used to describe language is the opposite of AE’s writing.

There’s a madness inside me dying to get out. They were scared of it when I was at art school and they taught me how to contain them / that / him? And I fell for it.

I fell for it.

I fell for him.

Oh falling falling falling, it’s always about falling.

Falling in love again,

Never wanted to

What am I to do

I can’t help it

I used to sing this in an exaggerated Dietrich way. I haven’t done so for a long time.

Revive this and record it and have it available on the QR

Q [uee] R code

uee

oooh eee

Choose piano music to go on the piano. I should have spoken to that student who was playing the piano. I didn’t talk to any of them, though I did imagine doing so and had imaginary conversations with them in my head. Imagined conversations are so much better, you can get the replies you want. I didn’t ask any of the students how they felt about the place, though I got a sense of how that was. There was a quiet and studious yet relaxed feeling about the place when I was in there. It seemed well liked. I could feel that. Some students working on their own, some in small groups discussing their studies. A nice group of about four or five of them at the sofas on the mezzanine at the garden side, having a chat but quietly, not hushed, just respectful of others. No one making a loud noise or laughing out loud or general huge hubbub going on. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve nothing against loud laughing, in fact, I once made a piece of work about it where I put a loud laugh in a safe with very thick walls and locked the door and the laugh spilled out. It was something about the fear of the ‘laugh of the medusa’ but on the other hand, if you’re wanting to get on with work you don’t really want a loud racket.

A loud racket – a loud (tennis) racket?

These are some pretty stream of consciousness notes, of which there is going to be quite a lot in the days that follow my trip, I think. Deciding I will risk putting these on the blog, unedited, the flow of ideas, how I am consumed by, possessed by the working out of the works and the exhibition. How it is constant work, how even in my sleep I am at it.

Oh, reminds me of a dream I just had before I got up of a beautiful double rainbow happening in a room, adjacent to the one I was in. In this adjacent room it was raining. By the time I got in there most of the rainbow had gone.

My trip – psychedelics. Ask K more about this. She is a consultant doctor friend whose specialism is pain, very knowledgeable and clever and very much into holistic approaches and frustrated by conventional medicine’s chopping up of the person into symptomatic parts for removal.

‘pain’, a faux ami, bread in French

holistic, holi-stick, holy stick

doctors as ‘removal men’ (and women, of course)

false friends, those friends who won’t let you be who you want to be and try to hold you back by bullying you if you show that you’re clever, girls, not wanting to be shown up for not trying by a girl who tries.

A trying girl. ‘She can be very trying at times’. Overheard conversations like the oh-so-significant one where AE hears her mother talking to a friend about her dead sister.

The books on the shelves could be in addition to Annie Ernaux’s. I could make a selection there – include Atwood’s Cat’s Eye, which I must reread.

I was going to do so much reading on the train but I just kept looking out of the window trying to capture the evanescent view. Or looking at my phone, communicating all the way with friends, silly stuff, sending them lists of all the snacks I had in my bag.

This trip, preoccupied when it came to the journey with planning the snacks I would take. Having provisions. A preoccupation inherited from war-time, when there wasn’t enough. Passed on by Granny and Mum. A safety net. Could have a snack stash in the exhibition. Vermin risk.

AE imbuing the place, a three dimensional palimpsest. I think what happens from now on in is going to be . . . it is all falling into place.

Falling into place. – yes, nothing can be suspended in case it falls on people’s heads. Even something light as a feather, which would give them a mild surprise if anything. Imagine a feather falling on your head, and how you would react. Would it require a trip to A and E? A video: a feather falling on your head and a completely over the top reaction, “ow!” or “ouch!” Blood perhaps? a bandage?

I can make a series of these video works viewable by QR code and put the QR code up somewhere. There are ample opportunities for putting things up, find the right space.

‘Vainglorious’ – that piece, could be remade as vinyl. Put up where it will cast a shadow.

How do you write the letter ‘ash’ on a keyboard? Practice it in a notebook. Find out all about it. Simples, hold down the a key then press 5

Routes you go down.

Free-standing piece, exercise books.

Books you exercise with. Weighted books. A heavy read. Difficult to pick up.

Dating: guys who are difficult to pick up. Have a really heavy man, it’s difficult to pick up. Put him out in the garden. Maybe stuff him with something which would get heavier when it rains. Make all this stuff.

Do these objects work physically or are they better as word-play, as ideas?

Golf. Ask M about golf.

Where my brain goes. Unfiltered.

Filtered coffee.

Not having to put it through the filter of trying to make it look beautiful, or ambiguous or like art. Perec, doesn’t AE like Perec? Les Choses. Read more Perec? Do I enjoy him or does he just get in the way of my own idea of fun, with his idea of fun? Do I enjoy a fun read? And Autobiographie des objets – Francois Bon

Can anyone else get anything out of your stream of consciousness thoughts? Does it matter?

Stream of consciousness. Could make that in the garden, with sparkly streamers, have it running down the slope, glinting in the sun. Put some in our garden here and see how it behaves? Need a slope which catches the rain. The idea of fashioning some ‘sculptures’ out of clay to place in the garden. They are about me ‘performing the artist’. I like examining that. In which ways do I still ‘perform the artist’? Kevin Atherton, he made performance works about that. I used to be Facebook friends with him, I could get in touch with him.

Getting in touch with people. Reaching out a finger-tip, like ET, to connect with people, like Michelangelo’s painting of the fingertip of god, Oh god, I ought to know what it’s called. Not Vitruvian man, the other one, the Sistine chapel one.

A stream of consciousness art history. Record it, like when people are asked to draw a map of the world and they make up where countries are and it’s funny.

FUNNY

HUMOUR

COMEDY

DON’T HIDE YOUR FUNNY BONES

Why would you?

Funny bones.

Amusing bones.

This is an interesting train of thought

Train of thought

This is an interesting train of thought I’ve been having all along: where is the humour in AE? There isn’t a whole lot and yet I love reading her. How and where I feel different from her and how and where we connect.

A love piece, a being-in-love-with her piece. Where I just let rip with my ‘relationship’ with her, with my imagined relationship with her. There is so much fantastic SEX in her works. She loves sex. Sex is celebrated. The young folk call it ‘sex positivity’ these days, don’t they. I find that sad. They have to distinguish when they are talking about sex as something good, because so much of the discussion is about abuse and ‘me too’ and sexual violence. How sad. Women’s love of women. Being alongside her in her sexual adventures. Distinction between sex and desire. Is it AE’s desire which comes across so strongly?

Will there be a catalogue to my show? Yes, I will make one.

All these little interventions, placed there. Here there and everywhere, like the Beatles song. Letting go of it having to be art or to be ‘like art’.

Elise and Fabien as muses. Companions. Collaborators. The journey is not lonely and solitary and hard and boring. It is fun and companionable and warm and sociable. The sun shines. If I can’t put the curtain up I’ll put it up elsewhere, against a beautiful blue sky and film it dancing in the breeze. Rose Finn-Kelcey’s flags ‘Power To The People’. Ah, Rose. Motor Neurone Disease took her. Such a closing down for such an opening up flower of a person.

Heartbreak at the heart of it all.

About everything.

Ha ha

Ha

Tour de France, Kraftwerk.

Breath.

Last gasp.

H

French for ‘aitch’ is ‘ash’

‘ash’ is the name for the obsolete vowel æ

Golf: putting balls into holes. The breasty golf-hole door flaps at the back entrance, or is that the front entrance? Turn that into a handy breasty golfy game. What are they and where do they go? Do something with them. Defo.

The architects like to make buildings where you don’t know which is the front and which is the back. Look up the architects. Sound like my kind of pranksters.

Marcel Broodthaers’ ‘Pense-Bête’ (‘Reminder’) made in 1964 same age as me and same number of years since AE’s abortion

hommage à

femmage after Miriam Schapiro. (https://madmuseum.org/views/unapologetic-feminine-excess)

dommage. – meaning ‘shame’, it’s a shame, what is the difference between la honte and le dommage? ask E and F?

c’est dommage

dammage

damage

damagée

dame-âgée

tbc